A Great Noise in Silver Spring

GREAT NOISE ENSEMBLE: Lullaby, Eulogy, Homage

Unitarian Universalist Church of Silver Spring

Hartke, Lash (world premiere), Reich

Sept. 9, 2011

Steve Reich, "Music for 18 Musicians"

review by Jason McCool for PinkLine Project

GREAT. A thing large, monumental, and in some cases unarguably cool.

NOISE. A thing raucous, unfiltered, and impolite.

ENSEMBLE. The suppressing of individual ego with a desire to create a collective thing richer and more expressive than might be possible for one.

The Great Noise Ensemble, perhaps the DC region’s most exciting professional group dedicated to performing new classical music, beautifully combined these elements into a poignant cocktail of solace and remembrance at the tranquil Unitarian Universalist Church of Silver Spring sanctuary Friday night. I beg your forgiveness for my effusiveness, dear readers; writing from a Brooklyn coffeeshop on this morning of 9/11/11, the air of ten years past hangs about like a ghostly curtain everywhere this weekend.

How does a commercially-saturated culture deal with tragedy and remembrance? In some ways it fails, which is why at times like these, so many of us look to art music, to things that seem timeless, driven by expression above salability. Music allows us to not only celebrate beauty and the very act of being alive, but community, recognizing the gifts of one another.

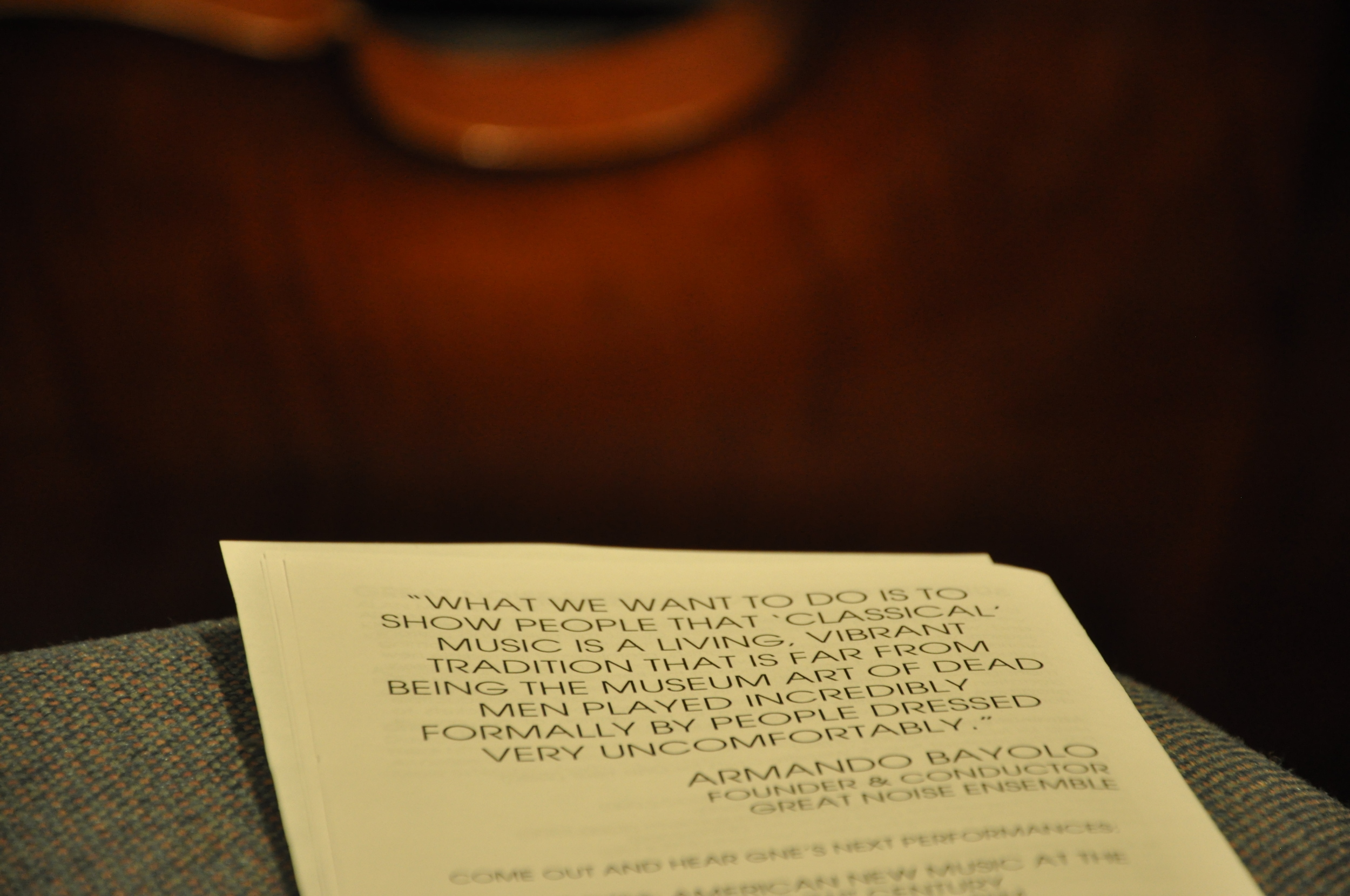

With the concert title “Lullaby, Eulogy, Homage,” GNE, founded by composer Armando Bayolo off a Craigslist posting (!) in 2005, handled this task with terrific subtlety, allowing the audience to fill the void with their own memories and intentions; apart from the title, the only specific reference to 9/11 was in Stephen Hartke’s composition “Beyond Words,” composed in the weeks following the catastrophe.

Hartke’s composition, thorny and more demanding than the mollification one generally receives from “in memoriam” pieces, opened the concert with a stark tone. Beginning with dark, dissonant chords played by string trio, the piece followed with what felt like disconnected chimes in the upper register of the piano, haunting, static, coolly reminiscent of the chamber works of Morton Feldman or Arvo Pärt. The work eventually progressed into “safer” tonal waters: lush, verdant chords making use of whole-tone harmonic motion, solidly concluding with a mere whisp of hope. My companion, unfamiliar with new music, remarked “I can’t believe how in sync all the performers were.”

Hannah Lash is a young composer, newly minted of the Eastman School of Music (I might’ve shared some shared alma mater tales with Ms. Lash, who was in attendance, had I realized this at the time!) and Harvard composition departments, already boasting an impressive resume of performances around the country. Ms. Lash’s gorgeous, playful work “Hush” was a world premiere, and it’s a testament to the growing national stature of GNE that they’re getting their hands on such primo new material. Composed for larger ensemble, “Hush” opened with electric celeste, bells, and high woodwinds, not far from the crystalline soundworld of Björk. Accompanied by an insistent, sort of “madcap nursery rhyme” pulse, Lush’s writing necessitates a disciplined maintenance of a steady beat amidst herky-jerky syncopations, and GNE was more than up to the task. The intense Chamber Symphony of John Adams came to mind as Lush’s work built toward a propulsive climax, petering out with harp tremolo and spidery, repetitive figures in the high celeste. New melodies harmonizing in muted trumpet and clarinet seemed to be asking direct questions of the audience, and I silently wondered “What do we learn about ourselves when we listen to this music?” My companion, becoming more familiar with new music, enthusiastically whispered “It’s like organized chaos.”

Enthusiasm for the first two unfamiliar works aside, the main draw of this evening for myself, and I imagine for many others in the packed house, was the rare chance to hear Steve Reich’s legendary “Music for 18 Musicians” performed live. (Check out a terrific glimpse of it here.) I vividly remember buying a used copy of the classic 1976 debut recording of this work while in college, and it’s one of a handful of pieces of music I know which genuinely stands as a “life changer.” I’m fascinated by how music functions in our lives, and this piece seems to have so many – admittedly, not unlimited to being a terrific sleep aid on more than one occasion! Alongside the better-known-in-the-mainstream work of Philip Glass, “Music for 18” is probably the most important work of 1970s minimalism, a popular musical movement which served to reintroduce performed classical music to large, curious music fans in NYC lofts. In some sense, this music served as a palette cleanser for audiences who had grown weary of much of the self-consciously dissonant, copycat new music too often allotted a larger stage than deserved (IMHO) within academic circles; this work in particular is an eminently listenable and “experience-able” work. I’ve always loved the cover art for the original 1976 ECM recording, whose intricate Oriental rug visually reflects one’s immersion into Reich’s famous “phase patterns.” Indeed, “Music for 18” seems almost easier to describe in visual terms; I’ve previously likened hearing the piece to one of those “3-D” posters everyone seemed to have on their dorm room walls in the early 90s, where once you’d relaxed and allowing your eyes to relax, you’d quite literally gain another perception.

GNE began the Reich like a bursting firecracker, faster and ballsier than I’m used to hearing it played on recordings, and sitting in the front row mere feet from the violinist and singers, pealing out single-tone strings of “loo-loo-loos” and “bup-bup-bups,” I almost felt a part of the music itself. I’m also sure I wasn’t the only audience member to actually feel the floor rumbling as the percussive pulse of Reich’s interweaving 6-beat phase patterns flew past. Hearing this piece live allowed a more clear vision of its unfolding architecture; of particular interest was watching the sections physically cued by various members of the ensemble, generally by a nod of the head or a subtly raised arm. (Amusingly, one percussionist felt “the swing” of the piece, smiling and almost dancing throughout.) Kudos to the performers for maintaining concentration over a 50+ minute work which features fiendishly difficult passages dependent on the sort of precision interaction only capable by well-trained musicians. (The interlocking double piano parts in one section particularly stood out.) As an audience member, one begins to relax and notice one’s breathing during this piece, and it becomes a sort of lived meditation through time. Tying back to the implied presence of 9/11, this immersion was deeply felt in the room; as “I” became united with the pounding rhythms, I felt a larger connection to beauty, memory, and community. And shouldn’t that be a major goal of “musicking,” as the (sadly, recently) late Christopher Small might say?